Students have gone on a rampage because of it. Schools have been shut down because of it. Academic sessions have been lost because of it. Even lives are sometimes lost because of it. Head, Education Desk, IYABO LAWAL examines the hike in tuition across state universities in the light of the recent crisis that rocked the Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba (AAUA).

Hike in school fees from time to time by state and federal universities has always been a contentious issue. In Nigeria when prices of goods go up, they hardly come down. You can ask the market people. But in Nigeria’s various institutions, especially universities, students have developed the knack of forcing the hands of authorities to bring down tuition anytime it is increased.

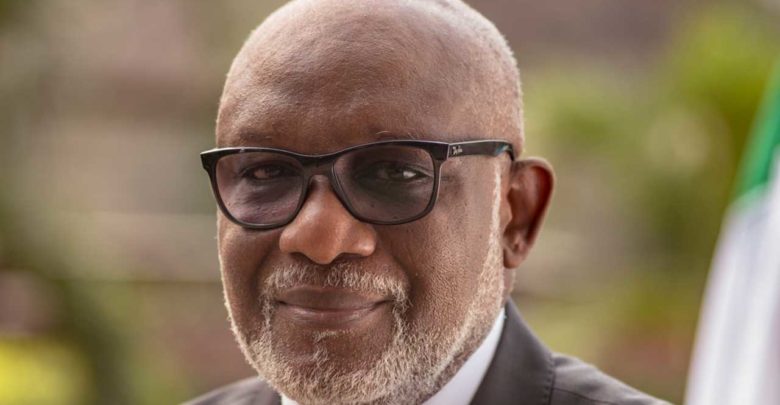

Few things touch the raw nerves of Nigerian students more than a hike in school fees. Take what happened in Ondo State as an example. In the wake of the announcement that the tuition of AAUA had been increased from N35, 000 to N200, 000, the students in unmistakable terms threatened to make the state ungovernable for the governor, Rotimi Akeredolu.

The student leaders of AAUA, with solidarity from the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS) and National Association of Ondo State Students (NAOSS) mobilised thousands of students to protest against the hike.

The students, who carried different placards, barricaded the Oba Adesida road causing a lot of traffic in Akure metropolis, as they expressed their displeasure against the increment and chanted anti-government songs.

The crisis at AAUA is a signpost of an issue that bedevils most state universities in Nigeria. In fact, many state universities are caricatures of their federal counterparts. With so-called lean purses of the chief executives of the various states across the nation, little or no attention is often paid to tertiary education. Funding universities is the least of their objectives. Thus, for most of those institutions, the only way to survive is the hard way: increase school fees arbitrarily from time to time.

In countries around the world, tuition can cost an arm and a leg. In Nigeria where an average citizen lives on less than $2 a day, the federal government has had to subsidise university education. But has that been enough? What can the country’s higher institutions do to keep the ivory tower running smoothly – without hiccups as occasioned by strike actions and sometimes violent protests?

Experts in tertiary education funding have noted that state government’s financial contributions to run the universities are hardly sufficient resulting in the government demanding that the universities should source for 10 per cent of the fund needed to keep running.

The need for alternative revenue generation by the universities was emphasised by the implementation committee of the national policy on education that the universities must devise means to be self-sustaining, and “use their internal reservoir of initiative and ingenuity in finding alternative options in the face of the challenges of financial stringency”.

Prof. Comfort Akomolafe and Mrs. Esther Aremu at the Ekiti State University, in their research on alternative sources of financing university education argued that funding remains vital to the provision of functional education that can lead to a national transformation.

They, however, said, “Unfortunately, there have been an outcry against poor funding of education in the country most especially at the university education level.”

Between 1990 and 1997, the real value of government allocation for university education had declined by 27 per cent even as enrolment grew by 77 per cent. For three years – between 2004 and 2006 – N196 billion was allocated to federal universities (which is only 14.8 per cent of the required N1.3249bn billion).

“This is despite the fact that Nigeria is currently witnessing increase enrolment of university students as provided,” the scholars added.

Some have claimed that inadequate funding of university education illustrates a lack of commitment to the future growth and transformation of the nation on the part of the government even though more than 90 per cent of university funding comes from the government.

In recent years, various tertiary institutions across the country had witnessed spikes in tuition.

Osun State University, from N95, 000 to N135, 500; Anambra State University, from N76, 000 to N139, 000; Lagos State University (LASU), from N96, 750 to N158, 250; Imo State University, from N120, 000 to N150, 000; Plateau State University, from N50, 000 to N100, 000 and University of Ilorin (UNILORIN) from N16, 000 to N75, 000.

For Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH), returning students who are indigenes of Oyo and Osun state will be paying N200, 000 while non-indigenes are to pay N250, 000 from N50, 000; Kwara State University (KWASU) first year students who are indigenes pay N99, 500.00, while 200-400Level students pay N109, 500.00. For non-indigenes, new students pay N200, 000 while others pay N210, 000 from the initial N65, 000 to N80, 000.

Enugu State University of Science and Technology (ESUT) students pay N124, 900 at all levels; Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti school fees for undergraduate full-time degree student is N77, 500, while part-time is N78, 000.

The aftermath has always been uproar, protests, closure of schools and reopening. But there has not been an effective solution to the crisis.

Increasing school fees in Nigeria’s tertiary institutions seems to be a pastime for state governors in the country and when Ondo State government chose to join the bandwagon of states that arbitrarily increase tuition, his territory almost boiled over. Thankfully, there is calm in the sunshine state for now.

Some have argued that if tertiary education is expensive, the lack of it can be disastrous, some stakeholders have said, urging higher institutions to look inward and devise means of not depending so much on the government’s bailouts and handouts.

In a presentation to the international community on ‘Public-private partnership and sustainable higher education funding: the Nigerian experience’, Prof. Bashiru Ademola Raji, a few years ago asked the question: how do Nigerian universities cope with these two key issues? The answers are not far-fetched.

According to the World Bank, higher institutions in sub-Saharan African countries like Nigeria face the formidable policy challenge of balancing the need to raise educational quality with increasing social demand for access. It said:

“The task of funding these institutions will become increasingly difficult in the years ahead, as the youth population continues to grow, each country will have to devise a financing approach to higher education development that enables it to meet the challenge.”

With average Nigerians living on less than one dollar a day and their representatives in public offices enjoying ostentatious lifestyles, the idea of increasing tuition or having tuition at all is considered amoral.

The argument is that public figures like the president, vice president, governors, and lawmakers, among others send their children to high-end private or foreign institutions while they allow public schools in Nigeria to deteriorate both in terms of academics and infrastructure. In view of this, Nigerians want free education up to the tertiary level.

Life as a Nigerian, they assert is pitiable as citizens have to provide their own community roads, water and generate their own electricity. More than ever before, public analysts claimed that it has become increasingly difficult for parents to fund the university education of their children.

Also, as Nigeria struggles in the face of economic instability, the issue of the federal government’s sole funding of university education and payment of tuition has come to the fore again.

That, however, did not sway Prof. Benson Osadolor’s view that tuition of public tertiary institutions should be reviewed as he was quoted as saying: “It is justified, of course, in terms of quality and the cost of education that we give to our children. University education in a country like Germany is free. Germany has enormous resources; the state actually contributes 100 per cent to the resources of the university system. We also have industries and foundations supporting the government’s efforts. This explains why they have high standards and good resources, particularly for teaching and learning.

“Here in Nigeria, a third-world country, the resources are not there. Students are crammed into very small lecture theatres. In some cases, they have no chairs, no benches, and tables. Do you think this can continue? No. We should sit down and reassess our future and the future of higher education in this country and think of what we can do to support the government’s efforts. We do not have foundations, institutions or organisations committing their resources to fund higher education in Nigeria.”

When the issue of fee hike was rife in 2017, the NANS President, Chinonso Obasi, had noted that the institutions and the government have always made students bear the brunt of “administrative ineptitude.”

“In saner climes, education funding includes revenue from researches and consultative collaborations. Implementation of UNESCO strategies, particularly commercialising research findings, should occupy Nigeria’s educational institutions rather than constant hike in tuition payable by hapless students.

NANS believes that the planned hike in fees would be the last straw that would break the cycle of obnoxious levy on learning and pursuit of education,” he had argued.

Obasi pointed out that such increase can jeopardise the future prospects of youths studying in various higher institutions.

He said, “If administrators of Nigeria’s educational institutions have run out of ideas of funding and sustaining educational institutions in the country, they should feel free to liaise with students to explore new ways of funding the institutions.

In April last year, the University of Ibadan was reported to have increased its accommodation and professional training fees for students –from N14, 000 to N40, 000 and N75, 000 to N100, 000 respectively while AAUA increased its school fees from about N35, 000 to between N120, 000 and N200, 000 per session.

But that did not sit down well with parents, students and the civil society. A human rights advocacy group, the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP), had urged the authorities of the schools to reverse the hike or face legal action.

“The universities ought to have carefully considered the effects of high fees on accessibility and the vision of education that they seek to achieve. The universities are advised to find solutions to their funding difficulties elsewhere.

“But if they fail to reverse these fees within seven days of the publication of this statement, SERAP would take appropriate legal action to compel them to do so,” the civil organisation warned.

It is believed that such a dramatic increase in academic fees can have the effect of “discriminating” against disadvantaged students who may be unable to pay the new fees, and who are not granted an exemption, “thereby creating a classification based on the economic and social status of their parents”.