Satellites to monitor whale strandings from space

- Scientists developing techniques to count great whales from space say the largest ever recorded mass stranding event was probably underestimated.

Scientists developing techniques to count great whales from space say the largest ever recorded mass stranding event was probably underestimated.

The carcasses of 343 sei whales were spotted on remote beaches in Patagonia, Chile, in 2015 – but this survey work was conducted from planes and boats, and carried out many weeks after the deaths actually occurred.

However, an analysis of high-resolution satellite images of the area taken much closer in time to the stranding has now identified many more bodies.

It’s difficult to give a precise total for the number of whales involved but in one sample picture examined by researchers, the count was nearly double.

The new investigation, published in the Plos One journal, was undertaken as a proof of principle exercise by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and various Chilean organisations.

It’s not easy to see an object, even one as large as a great whale, from several hundred kilometres up in space, but the international team believes the capability of modern satellites now makes this a practical task.

Being able to detect strandings more effectively will inform the ongoing conservation of whales. It will also flag potentially deteriorating ocean conditions, something the fishing industry for example will be keen to know about.

The monitoring of whales from orbit is set therefore to become a powerful tool with which to assess the state of the environment.

“The technology is getting better all the time,” said Dr Carlos Olavarría from the Centre for Advanced Studies in Arid Zones (CEAZA), La Serena, Chile.

“In this study, we were using 50cm resolution images, but the satellites now can see 30cm. In the future, we’d like also to be able to analyse the pictures automatically, rather than manually; and I’m sure as more minds are applied to the problem, this will become possible,” he told BBC News.

What happened in the stranding event?

It’s not clear why such a large number of sei whales beached en masse in early 2015. One reason for the uncertainty is that researchers were very late in getting to the scene to run tests to establish the cause.

That was in part because the stranding occurred in a very thinly populated, and difficult to access, area of central Patagonia called the Gulf of Penas. It has multiple fjords, channels and islands, and the deaths only came to light by accident when an unrelated expedition chanced on the carcasses.

This was a good month after the event and by then the sei whales had already started to decompose. Nonetheless, a ground team’s inquiries led it to the conclusion that the cetaceans had probably been poisoned after consuming toxic algae.

How did the satellites gauge the event’s size?

The planes and boats that surveyed the Gulf of Penas counted more than 340 dead whales, but the complex geography meant that some bodies almost certainly were missed.

“The aerial survey was done on a huge scale and was very impressive, but it’s possible some of the carcasses got washed back out to sea in storms and simply weren’t counted. The 343 number was only ever a best estimate,” said BAS whale expert Dr Jennifer Jackson.

The high-resolution satellite imagery allowed scientists to do a count much closer in time to the event itself.

The researchers used pictures from the WorldView-2 spacecraft which can discern features larger than 50cm across from an altitude of 700km. For a whale that may be 10-15m in length, this produces a good outline of the animal’s overall shape, including its distinctive fluke.

The team examined two archive images of the gulf from mid-March in 2015. In one, they counted slightly fewer whales than in the aerial survey work; but substantially more in the second picture.

So, how useful is satellite observation?

It’s possible to see the big baleen whales, like the sei whale, from orbit, and with the WorldView series of satellites now offering 30cm resolution, the task should become even easier – and for smaller whale species too, not just the baleens.

Scientists could monitor any beach in world, but especially those remote coastlines where cetacean strandings are a regular occurrence – in places such as Tasmania, New Zealand, the Falkland Islands, and obviously South American Patagonia.

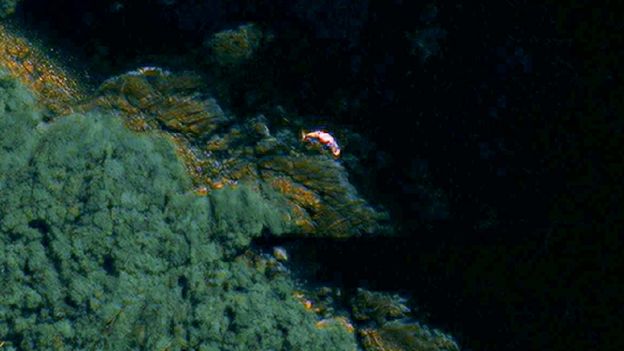

But it would be even easier if an automated detection system could be developed. The team tried this by training a computer to look for the spectral (light) signature of a dead whale in the Gulf of Penas (the seis turned pink and orange as they decomposed).

However, this approach was less successful than manual inspection of the pictures. The algorithms, though, are bound to improve.

“There are many more satellites planned to be launched with 50cm and 30cm resolution, so if we could automate the system it might be able to find these stranding events almost as they happen,” BAS remote sensing specialist Peter Fretwell told BBC News.

How will whales benefit from this science?

Getting to the scene of a stranding quickly will give greater certainty to the cause of an event. Sei whales have continued to wash up in the Gulf of Penas every year since 2015 and so it’s vital scientists understand fully what’s happening off-shore.

Strandings more widely can be useful markers of the status of a population. The dissection of washed-up bodies (a necropsy) will be an opportunity to investigate the general health of animals, and to study aspects of their behaviour such as their dietary habits.

Even just the pattern of strandings will provide information on which whales are present in an area and their likely numbers. All this detail is facilitated by a more rapid response.

“It’s important ecologically,” commented Andrew Baillie, the Cetacean Strandings Officer at London’s Natural History Museum.

“[Whales] are often top predators and they are very involved in the marine ecosystem. If they are suffering because of any actions of humans then we need to monitor that and mitigate it if possible.”